Feed: Matt Segal

Entries found: 22

How I hunt down (and fix) errors in production

Published: 2022-05-03T12:00:00+10:00

Updated: 2022-05-03T12:00:00+10:00

UTC: 2022-05-03 02:00:00+00:00

URL: https://mattsegal.dev/prod-bug-hunt.htmlOnce you’ve deployed your web app to prod there is a moment of satisfaction: a brief respite where you can reflect on your hard work. You sit, adoringly refreshing the homepage of www.mysite.com to watch it load over and over. It’s beautiful, perfect, timeless. A glittering …Content Preview

Once you’ve deployed your web app to prod there is a moment of satisfaction: a brief respite where you can reflect on your hard work. You sit, adoringly refreshing the homepage of www.mysite.com to watch it load over and over. It’s beautiful, perfect, timeless. A glittering crystal palace of logic and reason. Then people start to actually use it in earnest and you begin to receive messages like this in Slack:

Hey Matt. I am not getting reply emails for case ABC123 Jane Doe

Ideally, with a solid monitoring stack , you will be alerted of bugs and crashes as they happen, but some may still slip through the cracks. In any case, you’ve got to find and fix these issues promptly or your users will learn to distrust you and your software, kicking off a feedback loop of negative perception. Best to nip this in the bud.

So a user has told you about a bug in production, and you’ve gotta fix it - how do you figure out what went wrong? Where do you start? In this post I’ll walk you through an illustrative example of hunting down a bug in our email system.

The problem

So this was the message I got over Slack from a user of my website:

Hey Matt. I am not getting reply emails for case ABC123 Jane Doe

A user was not receiving an email, despite their client insisting that they had sent the email. That’s all I know so far...

More detail

... and it’s not quite enough. I know the case number but that’s not enough to track any error messages efficiently. I followed up with my user to check:

- what address was used to send the email (eg. jane.doe@gmail.com)

- when they attempted to send the email (over the weekend apparently)

With this info in hand I can focus my search on a particular time range and sender address.

Knowledge of the system

There’s one more piece of info you need to have before you start digging into log files and such: what are the components of the email-receiving system? I assembled this one myself, but under other circumstances, in a team setting, I might ask around to build a complete picture of the system. In this case it looks like this:

In brief:

- The client sends an email from their email client

- The email travels through the mystical email realm

- SendGrid (SaaS product) receives the email via SMTP

- SendGrid sends the email content to a webhook URL on my webserver as an HTTP POST request

- My web application ingests the POST request and stores the relevant bits in a database table

Inside the web server there’s a pretty standard “3 tier” setup:

- NGINX receives all web traffic, sends requests onwards to the app server

- Gunicorn app server running the Django web application

- A database hosting all the Django tables (including email content)

My approach

So, the hunt begins for evidence of this missing email, but where to start looking? One needs a search strategy. In this case, my intuition is to check the “start” and “end” points of this system and work my way inwards. My reasoning is:

- if we definitely knew that SendGrid did not receive the email, then there’d be no point checking anywhere downstream (saving time)

- if we knew that the database contained the email (or it was showing up on the website itself!) then there’d be no point checking upstream services like SendGrid or NGINX (saving time)

So do you start upstream or downstream? I think you do whatever’s most convenient and practical.

Of course you may have a special system-specific knowledge that leads you towards checking one particular component first (eg. “our code is garbage it’s probably our code, let’s check that first”), which is a cool and smart thing to do. Gotta exploit that domain knowledge.

Did SendGrid get the email?

In this case it seemed easiest to check SendGrid’s fancy web UI for evidence of an email failing to be received or something. I had a click around and found their reporting on this matter to be... pretty fucking useless to be honest.

This is all I could find - so I’ve learned that we usually get emails. Reassuring but not very helpful in this case. They have good reporting on email sending, but this dashboard was disappointingly vague.

Is the email in the database?

After checking SendGrid (most upstream) I then checked to see if the the database (most downstream) had received the email content.

As an aside, I also checked if the email was showing up in the web UI, which it wasn’t (maybe my user got confused and looked at the wrong case?). It’s good to quickly check for stupid obvious things just in case.

Since we don’t have a high volume of emails I was able to check the db by just eyeballing the Django admin page. If we were getting many emails per day I would have instead run a query in the Django shell via the ORM (or run an SQL query directly on the db).

It wasn’t there >:(

Did my code explode?

So far we know that maybe SendGrid got the email and it’s definitely not in the database. Since it was easy to do I quickly scanned my error monitoring logs (using Sentry ) for any relevant errors. Nothing. No relevant application errors during the expected time period found.

Aside : yes my Sentry issue inbox is a mess. I know, it's bad. Think of it like an email in box with 200 unread emails, most of them spam, but maybe a few important ones in the pile. For both emails and error reports, it's best to have a clean inbox.

Aside : ideally I would get Slack notifications for any production errors and investigate them as they happen but Sentry recently made Slack integration a paid feature and I haven’t decided whether to upgrade or move.

Did NGINX receive the POST request?

Looking back upstream, I wanted to know if I could find anything interesting in the NGINX logs. If you’re not familiar with webserver logfiles I give a rundown in this article covering a typical Django stack.

All my server logs get sent to SumoLogic, a log aggregator (explained in the “log aggregation” section of this article ), where I can search through them in a web UI.

I checked the NGINX access logs for all incoming requests to the email webhook path in the relevant timeframe and found nothing interesting. This shows NGINX is receiving email data in general, which is good.

Next I checked the NGINX error logs... and found a clue!

For those who don’t want to squint at the screenshot above this was the error log:

2022/04/30 02:38:40 [error] 30616#30616: *129401 client intended to send too large body: 21770024 bytes, client: 172.70.135.74, server: www.mysite.com, request: "POST /email/receive/ HTTP/1.1", host: "www.mysite.com”

This error, which occurs when in receiving a POST request to the webhook URL, lines up with the time that the client apparently sent the email. So it seems likely that this is related to the email problem.

What is going wrong?

I googled the error message and found this StackOverflow post . It seems that NGINX limits the size of requests that it will receive (which is configurable via the nginx.conf file). I checked my NGINX config and I had a limit of 20MB set. Checking my email ingestion code, it seems like all the file attachments are included in the HTTP request body. So... my guess was that the client sending the email attached more than 20MB of attachments (an uncompressed phone camera image is ~5MB) and NGINX refused to receive that request. Most email providers (eg Gmail) offer ~25MB of attachments per email.

Testing the hypothesis

I actually didn’t do this because I got a little over-exicted and immediately wrote and pushed a fix.

What I should have done is verified that the problem I had in mind actually exists. I should have tried to send a 21MB email to our staging server to see if I could reproduce the error, plus asked my user to ask the client if she was sending large files in her email.

Oops. A small fuckup given I think the error message is pretty clear about what the problem is.

The fix

The fix was pretty simple, as it often is in these cases, I bumped up the NGINX request size limit (

client_max_body_size) to 60MB. That might be a little excessive, perhaps 30MB would have been fine, but whatever. I updated the config file in source control and deployed it to the staging and prod environments. I tested that I can send larger files by sending a 24MB email attachment to the staging server.Aftermath

We’ve asked the client to re-send her email. Hopefully it comes through and all is well.

I checked further back in the SumoLogic and this is not the first time this error has happened, meaning we’ve dropped a few emails. I’ll need to notify the team about this.

If I had more time to spend on this project and I’d consider adding some kind of alert to NGINX error logs so that we’d see them pop up in Slack - maybe SumoLogic offers this, I haven’t checked.

Another option would be going with an alternative to SendGrid that had more useful reporting on failed webhook delivery attempts.

Overview

Although it can sometimes be stressful, finding and fixing these problems can also be a lot of fun. It’s like a detective game where you are searching for clues to crack the case.

In summary my advice for productively hunting down errors in production are:

- Gather info from the user who reported the error

- Mentally sketch a map of the system

- Check each system component for clues, using a search strategy

- Use these clues to develop a hypothesis about what went wrong

- Test the hypothesis if you can (before writing a fix)

- Build, test, ship a fix (then check it's fixed)

- Tell your users the good news

Importantly I was only able to solve this issue because I had access to my server log files. A good server monitoring setup makes these issues much quicker and less painful to crack. If you want to know what montioring tools I like to use in my projects, check out my Django montioring stack .

How to setup Django with Pytest on GitHub Actions

Published: 2022-01-13T12:00:00+11:00

Updated: 2022-01-13T12:00:00+11:00

UTC: 2022-01-13 01:00:00+00:00

URL: https://mattsegal.dev/django-with-pytest-on-github-actions.htmlSomeone recently asked me When is a good time to get automated testing setup on a new Django project? The answer is "now". There are other good times, but now is best. In this post I'll briefly make my case for why, and show you an example of a minimal …Content Preview

Someone recently asked me

When is a good time to get automated testing setup on a new Django project?

The answer is "now". There are other good times, but now is best. In this post I'll briefly make my case for why, and show you an example of a minimal setup of Django running tests with pytest with fully automated continuous integration (CI) using GitHub Actions .

As soon as you know a Django project is going to be "serious", then you should get it set up to run tests. So, potentially before you write any features. My approach is to get testing setup and to write a dummy test or two and then get it running in CI. This means that as soon as you start writing features then you will have everything you need to write a real test and have it run automatically on every commit.

The alternate scenario is you start adding features and get swept up in that process. At some point you'll think "hmm maybe I should write a test for this...", but if you don't have tests and CI set up already then you're more likely to say "nah, fuck it I'll do it later" and not write the test. Getting pytest to work with Django on GitHub actions is pretty easy these days. Bite the bullet, it tastes better than you may expect.

Or you could just not write any tests. This is fine for small personal projecs. Tests are a lot of things but they're not fun. For more serious endeavours though, not having tests will lead to riskier deployments, longer feedback loops on errors and less confidence in making big changes. Have you ever done a huge, wild refactor of a chunk of code, followed by a set of passing tests? It feels great man, that's when you're really living.

The other question is: when should I run my tests? Sometimes you forget or you can't be bothered. This is where GitHub Actions (or any other CI) is very useful. You can set this service up to automatically run your tests every time you push a commit up to GitHub.

Let's go then: how do you set up Django + pytest + GitHub Actions? All the code discussed here can be found in this example GitHub repository .

Installation

Alongside Django you will need to install

pytestandpytest-django. These libraries are not required to run tests with Django: the official docs show you how to use Python's unittest library instead. I like pytest better though, and I think you will too. My requirements.txt file looks like this:django pytest pytest-djangoI don't pin my dependencies because I'm lazy: what can I say? I recommend you setup a virtual environment and then install as follows:

pip install -r requirements.txtConfiguraton

You can configure pytest with a standard pyproject.toml file. Here's mine . The most important thing is to set

DJANGO_SETTINGS_MODULEso pytest knows which settings to use. It's good to have a separate set of test settings for your project so that you can avoid, for example, accidently changing your production environment with credentials stored in settings when you run a test.[tool.pytest.ini_options] DJANGO_SETTINGS_MODULE = "demo.settings" filterwarnings = [ "ignore::UserWarning", ]This file should live in whichever folder you will be running

pytestfrom. For the reference project, that means in the./appfolder alongsidemanage.py.Adding a dummy test

That's a good start. Now we can test the setup so far with a dummy test. This test does nothing: it always passes, but it verifies that all the plumbing is working. In pytest, tests are just functions that use assert statements to check things:

def test_nothing(): """A dummy test""" assert TruePytest looks for a

testsfolder in your Django apps. For example, here is the tests folder in the reference project. So this dummy test function could live in a file namedapp/web/tests/test_dummy.py. You can add as many tests to a file as you like, or have as many test files as you like. Avoid duplicate names though!Running the tests locally

At this stage it's good to check that the dummy test works by running pytest from the command line:

pytest -vvRead

-vvas "very verbose". Here are specific instructions for anyone trying out the reference project. Hopefully that worked. You may see a folder called.pytest_cacheappear in your project. I recommend you gitignore this.Now let's add some more meaningful example tests before we move on to setting up GitHub Actions.

Adding a basic view test

My reference project has a very basic view named "goodbye" which just returns the text "Goodbye world". Here it is:

def goodbye_view(request): return HttpResponse(f"Goodbye world")You can test that this view returns the expected response using the Django test client . Pytest has a handy feature called fixtures , which is a little piece of magic where you ask for an speficic object via the test function arguments and pytest automagically provides it. In this case we add "client" to the function arguments to get a test client. It's a little out of scope for this post, but you can write your own fixtures too!

def test_goodbye_view(client): """Test that goodbye view works""" # Build the URL from the url's name url = reverse("goodbye") # Make a GET request to the view using the test client response = client.get(url) # Verify that the response is correct assert response.status_code == 200 assert response.content == b"Goodbye world"Very nice, but you will find that you need to do a little more work to test views that include database queries.

Adding a view test with database interaction

With pytest-django you need to explicitly request access to the database using the pytest.mark.django_db decorator. Below is an example of a test that hits the database. In this example there is a page view counter that increments +1 every time someone views the page:

def hello_view(request): counter, _ = PageViewCount.objects.get_or_create(title="hello") counter.count += 1 counter.save() return HttpResponse(f"Hello world. The counter is: {counter.count}")So if you load the page over and over again it should say:

Hello world. The counter is: 1 Hello world. The counter is: 2 Hello world. The counter is: 3 Hello world. The counter is: 4 ... etcHere is a test for this view:

import pytest from django.urls import reverse from web.models import PageViewCount @pytest.mark.django_db def test_hello_view(client): url = reverse("hello") assert PageViewCount.objects.count() == 0 response = client.get(url) assert response.status_code == 200 assert PageViewCount.objects.count() == 1 counter = PageViewCount.objects.last() assert counter.count == 1 assert b"Hello world" in response.content assert b"The counter is: 1" in response.content response = client.get(url) assert response.status_code == 200 counter.refresh_from_db() assert counter.count == 2 assert b"The counter is: 2" in response.contentSetting up GitHub Actions

Ok so all our tests are running locally, how do we get them to run automatically in GitHub Actions? You can configure an action by adding a config file to your GitHub project at the location

.github/workflows/whatever.yml. I named mine tests.yml .Let's walk through the contents of this file (docs here ):

# The name of the action name: Django Tests # When the action is triggered on: push: branches: - master pull_request: branches: - master # What to do when the action is triggered jobs: # A job called 'build' - arbitrary build: # Run on a Ubuntu VM runs-on: ubuntu-latest steps: # Checkout the GitHub repo - uses: actions/checkout@v2 # Install Python 3.8 - name: Set up Python 3.8 uses: actions/setup-python@v2 with: python-version: "3.8" # Pip install project dependencies - name: Install dependencies run: | python -m pip install --upgrade pip pip install -r requirements.txt # Move into the Django project folder (./app) and run pytest - name: Test with pytest working-directory: ./app run: pytest -vvThat's it, now pytest will run on every commit to master, and every pull request to master. You can see the actions for the reference project here . Every test run will put a little tick or cross in your GitHub commit history.

You can also embed a nice little badge in your README:

Conclusion

I hope this post helps you get started with writing and running automated tests for your Django project. They're a real lifesaver. If you liked this post about testing, you might also like this post about different testing styles ( There's no one right way to test your code ) and this post about setting up pytest on GitHub actions, without Django ( Run your Python unit tests via GitHub actions ).

My (free) Django monitoring stack for 2022

Published: 2022-01-01T12:00:00+11:00

Updated: 2022-01-01T12:00:00+11:00

UTC: 2022-01-01 01:00:00+00:00

URL: https://mattsegal.dev/django-monitoring-stack.htmlYou've built and deployed a website using Django. Congrats! After that initial high of successfully launching your site comes the grubby work of fixing bugs. There are so many things that can will go wrong. Pages may crash with 500 errors in prod, but not locally. Some offline tasks never …Content Preview

You've built and deployed a website using Django. Congrats! After that initial high of successfully launching your site comes the grubby work of fixing bugs. There are so many things that

canwill go wrong. Pages may crash with 500 errors in prod, but not locally. Some offline tasks never finish. The site becomes mysteriously unresponsive . This one pain-in-the-ass user keeps complaining that file uploads "don't work" but refuses to elaborate further: "they just don't work okay!?!".If enough issues crop up and you aren't able to solve them quickly and decisively, then you will lose the precious trust of your coworkers or clients. Often reputational damage isn't caused by the bug itself, but by the perception that you have no idea what's going on.

Imagine that you are able to find out about bugs or outages as they happen . You proactively warn your users that the site is down, not the other way around. You can quickly reproduce problems locally and push a fix to prod in a matter of hours. Sounds good right? You're going to need a good "monitoring stack" to achieve this dream state of omniscient hyper-competence.

You'll need a few different (free) tools to get a holistic picture of what your Django app is doing:

- Uptime monitoring : tells you when the site is down ( StatusCake )

- Error reporting : tells you when an application error occurs, collects details ( Sentry )

- Log aggregation : allows you to read about what happened on your servers ( Sumologic )

- Performance : tells you how long requests took, what's fast, what's slow ( Sentry , New Relic )

In the rest of this post I'll talk about these SaaS tools in more detail and why I like to use the ones linked above.

Uptime monitoring

It's quite embarrasing when your site goes down, but what's more embarrasing is when you learn about it from someone else . An uptime monitoring service can help: it sends a request to your site every few minutes and pings you (Slack, email) when it's unresponsive. This allows you to quickly get your site back online, hopefully before anyone notices. If you want to get fancy you can build a health check route (eg.

/health-check/) into your Django app which, for example, checks that the database, or cache, or whatever are still online as well.Another benefit of uptime monitoring is that you'll get a clear picture of when the outage started. For example, in the picture below you can see that a website of mine stopped responding to requests between ~21:00 and ~23:30 UTC. You can use this knowledge of exactly when the site become unresponsive to check other sources of information, such as server logs or error reports for clues.

I like to use StatusCake for this function because it's free, simple and easy to set up.

Error reporting

There are lots of ways for your site to break that don't render it completely unresponsive. A user might click a button to submit a form and receive a 500 error page because you made some trivial coding mistake that wasn't caught by your automated testing pipeline . This user comes to you and complains that "the site is broken". Sometimes they will provide you with a very detailed explanation of what they did to produce the error, which you can use to replicate the issue, but as often as not they may, infuriated by your shitty website and seemingly antagonistic line of questioning, follow up with "iTs JuST brOken OKAY!?". Wouldn't it be nice to get the detailed information that you need to fix the bug without having to talk to a human?

This is where error reporting comes in. When your Django web app catches some kind of exception, then an error reporting library can inspect the error and send the details to a SaaS service which records it for you. These error reporting tools capture heaps of useful information, such as:

- When the error happened first and most recently

- The exception type and message

- Which line of code triggered the error

- The stack trace of the error

- The value of local variables in each frame of the stack trace

- The Python version, package versions, user browser, IP, etc etc etc.

This rich source of information makes error reporting a vital tool. It really shines when you encounter errors that only happen in production, where you have no idea how to replicate them locally. Sentry is great for this task because it's free, easy to set up and has a great web UI. You can set up Sentry to send you error alerts via Slack and/or email.

Log aggregation

Production errors can be more complicated than a simple Python exception crashing a page. Sometimes, much more complicated. If you want to get a feel for the twisted shit computers will get up to then give Rachel by the Bay a read. To solve the trickier issues in production you're going to need to reconstruct what actually happened at the time of the error. You'll need to draw upon multiple sources of information, such as:

- application logs (eg. Django logs )

- webserver logs (eg. NGINX, Gunicorn logs )

- logs from other services (eg. Postgres, syslog, etc)

You can

sshinto your server and read these logs from the command line usinglessorgreporawkor something. Even so, it's much more convenient to access these logs via a log aggregation service's web UI, where you can run search queries to quickly find the log lines of interest. These tools work by running a "logging agent" on your server, which watches files of interest and sends them to a centralised server.

This model is paritcularly valuable if you have transient infrastructure (servers that don't last forever) or if you have many different servers, or if you want to limit

sshaccess for security reasons.Sumologic if my favourite free SaaS for this task because it's easy to install the logging agent and add new files to be watched. The search is pretty good as well. The main downside is that web UI can be a little complicated and overwhelming at times. The search DSL is very powerful but I always need to look up the syntax. Log retention times seem reasonable, 30 days by default. The Sumologic agent seems to consume several hundred MB of RAM (~300MB?).

Papertrail is, in my opinion, worse than Sumologic in every way I can think of. However, it is also free and presents a simple web UI for viewing and searching your logs. If you're interested I wrote about setting up Papertrail here . New Relic offer a logging service as well - never tried it though. There are open source logging solutions like Elasticsearch + Kibana and other alternatives, but they come with the downside of having to run them yourself: "now you have two problems".

Performance montioring

Sometimes your website isn't broken per-se, but it's too slow. People hate slow websites. You can often diagnose and fix these issues locally using tools like Django Debug Toolbar (I made a video on how to do this here ), but sometimes the slowness only happens in production. Furthermore, riffing on the general theme of this article, you want to know about (and fix) slow pages before your boss walks over to your desk and complains about it.

Performance monitoring tools instrument your Django web app and record information about how long various requests take. What's fast? What's slow? Which pages have problems? I recommend that you start out by using Sentry for this task because their performance monitoring service comes bundled with their error reporting by default. It's kind of basic, but maybe that's all you need.

The best appilcation performance monitoring for Django that I know of is New Relic's offering , which seems to have a free tier. The request traces that they track include a very detailed breakdown of where the time was spent in serving a request. For example, it will tell you how much time was spent querying the database, or a cache, or building HTML templates. Sometimes you need that level of detail to solve tricky performance issues. The downside of using New Relic is that you have to reconfigure your app server to boot using their agent as a wrapper.

Although it's not strictly on-topic, PageSpeed Insights is pretty useful for checking page load performance from a front-end perspective. If you're interested in more on Django web app performance then you might like this post I wrote, where I ponder: is Django too slow?

Conclusion

This list is not exhaustive or definitive, it's just the free-tier tools that I like to use for my freelance and personal projects. Nevertheless I hope you find them useful. It can be a pain to integrate them all into your app, but over the long run they'll save you a lot of time and energy.

Be prepared!

DevOps in academic research

Published: 2021-11-21T12:00:00+11:00

Updated: 2021-11-21T12:00:00+11:00

UTC: 2021-11-21 01:00:00+00:00

URL: https://mattsegal.dev/devops-academic-research.htmlI'd like to share some things I've learned and done in the 18 months I worked as a "Research DevOps Specialist" for a team of infectious disease epidemiologists. Prior to this job I'd worked as a web developer for four years and I'd found that the day-to-day had become quite …Content Preview

I'd like to share some things I've learned and done in the 18 months I worked as a "Research DevOps Specialist" for a team of infectious disease epidemiologists . Prior to this job I'd worked as a web developer for four years and I'd found that the day-to-day had become quite routine. Web dev is a mature field where most of the hard problems have been solved. Looking for something new, I started a new job at a local university in early 2020. The job was created when my colleagues wrote ~20k lines of Python code and then found out what a pain in the ass it is to maintain a medium-sized codebase. It's the usual story: the code is fragile, it's slow, it's easy to break things, changes are hard to make. I don't think this situation is anyone's fault per-se: it arises naturally whenever you write a big pile of code.

In the remainder of this post I'll talk about the application we were working on and the awesome, transformative, <superlative> power of:

- mapping your workflow

- an automated test suite

- performance improvements

- task automation

- visualisation tools; and

- data management

If you're a web developer, you might be interested to see how familar practices can be applied in different contexts. If you're an academic who uses computers in your work, then you might be interested to learn how some ideas from software development can help you be more effective.

The application in question

We were working on a compartmental infectious disease model to simulate the spread of tuberculosis. Around March 2020 the team quickly pivoted to modelling COVID-19 as well (surprise!). There's documentation here with examples if you want to poke around.

In brief, it works like this: you feed the model some data for a target region (population, demographics, disease attributes) and then you simulate what's going to happen in the future (infections, deaths, etc). This kind of modelling is useful for exploring different scenarios, such as "what would happen if we closed all the schools?" or "how should we roll out our vaccine?". These results are presented to stakeholders, usually from some national health department, via a PowerBI dashboard. Alternatively the results are included in a fancy academic paper as graphs and tables.

(Note: "notifications" are the infected cases that we know about)

A big part of our workflow was model calibration. This is where we would build a disease model with variable input parameters, such as the "contact rate" (proportional to how infectious the disease is), and then try to learn the best value of those parameters given some historical data (such as a timeseries of the number of cases). We did this calibration using a technique called Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC). MCMC has many nice statistical properties, but requires running the model 1000 to 10,000 times - which is quite computationally expensive.

This all sounds cool, right? It was! The problem is that when I started. the codebase just hadn't been getting the care it needed given its size and complexity. It was becoming unruly and unmanageable. Trying to read and understand the code was stressing me out.

Furthermore, running calibrations was slow . It could take days or weeks. There was a lot of manual toil where someone needed to upload the application to the university computer cluster, babysit the run and download the outputs, and then post-process the results on their laptop. The execution of the code itself took days or weeks. This time-sink is a problem when you're trying to submit an academic paper and a reviewer is like "hey can you just re-run everything with this one small change" and that means re-running days or weeks of computation.

So there were definitely some pain points and room for improvement when I started.

Improving our workflow with DevOps

The team knew that there were problems and everybody wanted to improve the way we worked. If I could point to any key factor in our later succeses it would be their willingness to change and openness to new things.

I took a "DevOps" approach to my role (it was in the job title after all). What do I mean by DevOps? This article sums it up well:

a set of practices that works to automate and integrate the processes between [different teams], so they can build, test, and release software faster and more reliably

Traditionally this refers to work done by Software Dev elopers and IT Op eration s , but I think it can be applied more broadly. In this case we had a software developer, a mathematician, an epidemiologist and a data visualisation expert working on a common codebase.

A key technique of DevOps is to think about the entire system that produces finished work. You want to conceive of it as a kind of pipeline to be optimised end-to-end, rather than focusing on any efficiencies achieved by individuals in isolation. One is encouraged to explicitly map the flow of work through the system. Where does work come from? What stages does it need to flow through to be completed? Where are the bottlenecks? Importantly: what is the goal of the system?

In this case, I determined that our goal was to produce robust academic research, in the form of published papers or reports. My key metric was to minimise "time to produce a new piece of research", since I believed that our team's biggest constraint was time, rather than materials or money or ideas or something else. Another key metric was "number of errors", which should be zero: it's bad to publish incorrect research.

If you want to read more about DevOps I recommend checking out The Phoenix Project and/or The Goal (the audiobooks are decent).

Mapping the workflow

As I mentioned, you want to conceive of your team's work as a kind of pipeline. So what was our pipeline? After chatting with my colleagues I came up with something like this:

It took several discussions to nail this process down. People typically have decent models of how they work floating around in their heads, but it's not common to write it out explicitly like this. Getting this workflow on paper gave us some clear targets for improvement. For example:

- Updating a model required tedious manual testing to check for regressions

- The update/calibrate cycle was the key bottleneck, because calibration ran slowly and manual steps were required to run long jobs on the compute cluster

- Post processing was done manually and was typically only done by the one person who knew the correct scripts to run

Testing the codebase

My first concern was testing. When I started there were no automated tests for the code. There were a few little scripts and "test functions" which you could run manually, but nothing that could be run as a part of continuous integration .

This was a problem. Without tests, errors will inevitably creep into the code. As the complexity of the codebase increases, it becomes infeasible to manually check that everything is working since there are too many things to check. In general writing code that is correct the first time isn't too hard - it's not breaking it later that's difficult.

In the context of disease modelling, automated tests are even more important than usual because the correctness of the output cannot be easily verified. The whole point of the system is to calculate an output that would be infeasible for a human to produce. Compare this scenario to web development where the desired output is usually known and easily verified. You can usually load up a web page and click a few buttons to check that the app works.

Smoke Tests

So where did I start? Trying to add tests to an untested codebase with thousands of lines of code is very intimidating. I couldn't simply sit down and write unit tests for every little bit of functionality because it would have taken weeks. So instead I wrote "smoke tests". A smoke test runs some code and checks that it doesn't crash. For example:

def test_covid_malaysia(): """Ensure the Malaysia region model can run without crashing""" # Load model configuration. region = get_region("malaysia") # Build the model with default parameters. model = region.build_model() # Run the model, don't check the outputs. model.run_model()To some this may look crimininally stupid, but these tests give fantastic bang-for-buck. They don't tell you whether the model outputs are correct, but they only takes a few minutes to write. These tests catch all sorts of stupid bugs: like someone trying to add a number to a string, undefined variables, bad filepaths, etc. They doesn't help so much in reducing semantic errors, but they do help with development speed.

Continuous Integration

A lack of testing is the kind of problem that people don't know they have. When you tell someone "hey we need to start writing tests!" the typical reaction is "hmm yeah sure I guess, sounds nice..." and internally they're thinking "... but I've got more important shit to do". You can try browbeating them by telling them how irresponsible they're being etc, but that's unlikely to actually get anyone to write and run tests on their own time.

So how to convince people that testing is valuable? You can show them, with the magic of ✨continuous integration✨. Our code was hosted in GitHub so I set up GitHub Actions to automatically run the new smoke tests on every commit to master. I've written a short guide on how to do this here .

This setup makes tests visible to everyone. There's a little tick or cross next to every commit and, importantly, next to the name of the person who broke the code.

With this system in place we eventually developed new norms around keeping the tests passing. People would say "Oops! I broke the tests!" and it became normal to run the tests locally and fix them if they were broken. It was a little harder to encourage people to invest time in writing new tests.

Once I become more familiar with the codebase I eventually wrote integration and unit tests for the critical modules. I've written a bit more about some testing approaches I used here .

Something that stood out to me in this process was that perhaps the most valuable thing I did in that job was one of the easiest things to do. Setting up continuous integration with GitHub took me an hour to two, but it's been paying dividends for ~2 years since. How hard something is to do and how valuable it is are different things.

Performance improvements

The code was too slow and the case for improving performance was clear. Slowness can be subjective, I've written a little about the different meanings of "slow" in backend web dev, but in this case having to wait 2+ days for a calibration result was obviously way too slow and was our biggest productivity bottleneck.

The core of the problem was that a MCMC calibration had to run the model over 1000 times. When I started, a single model run took about 2 minutes. Doing that 1000 times means ~33 hours of runtime per calibration. Our team's mathematician worked on trying to make our MCMC algorithm more sample-efficient, while I tried to push down the 2 minute inner loop.

It wasn't hard to do better, since performance optimisation hadn't been a priority so far. I used Python's cProfile module, plus a few visualisation tools to find the hot parts of the code and speed them up. This article was a lifesaver. In broad strokes, these were the kinds of changes that improved performance:

- Avoid redundant re-calculation in for-loops

- Switching data structures for more efficient value look-ups (eg. converting a list to a dict)

- Converting for-loops to matrix operations ( vectorisation )

- Applying JIT optimisation to hot, pure, numerical functions ( Numba )

- Caching function return values ( memoization )

- Caching data read from disk

This work was heaps of fun. It felt like I was playing a video game. Profile, change, profile, change, always trying to get a new high score. Initially there were lots of easy, huge wins, but it became harder to push the needle over time.

After several months the code was 10x to 40x faster, running a model in 10s or less, meaning we could run 1000 iterations in a few hours, rather than over a day. This had a big impact on our ability to run calibrations for weekly reports, but the effects of this speedup were felt more broadly. To borrow a phrase: "more is different". Our tests ran faster. CI was more snappy and people were happier to run the tests locally, since they would take 10 seconds rather than 2 minutes to complete. Dev work was faster since you could tweak some code, run it, and view the outputs in seconds. In general, these performance improvements opened up other opportunities for working better that weren't obvious from the outset.

There were some performance regressions over time as the code evolved. To try and fight these slowdowns I added automatic benchmarking to our continuous integration pipeline.

Task automation

Once our calibration process could run in hours instead of days we started to notice new bottlenecks in our workflow. Notably, running a calibration involved a lot of manual steps which were not documented, meaning that only one person knew how to do it.

Interacting with the university's Slurm cluster was also a pain. The compute was free but we were at the mercy of the scheduler, which decided when our code would actually run, and the APIs for running and monitoring jobs were arcane and clunky.

Calibrations didn't always run well so this cycle could repeat several times before we got an acceptable result that we would want to use.

Finally, there wasn't a systematic method for recording input and output data for a given model run. It would be hard to reproduce a given model run 6 months later.

The process worked something like this when I started:

It was possible to automate most of these steps. After a lot of thrashing around on my part, we ended up with a workflow that looks like this.

In brief:

- A disease modeller would update the code and push it to GitHub

- Then they could load up a webpage and trigger a job by filling out a form

- The calibration and any other post processing would run "in the cloud"

- The final results would be available on a website

- The data vis guy could pull down the results and push them to PowerBI

There were many benefits to this new workflow. There were no more manual tasks. The process could be run by anyone on the team. We could easily run multiple calibrations in parallel (and often did). We also created standard diagnostic plots that would be automatically generated for each calibration run (similar to Weights and Biases for machine learning). For example, these plots show how the model parameters change over the course of a MCMC calibration run.

I won't go into too much detail on the exact implementation of this cloud pipeline. Not my cleanest work, but it did work. It was a collection of Python scripts that hacked together several tools:

- Buildkite for task automation (it's really great)

- AWS EC2 for compute

- AWS S3 for storing data

- boto3 for managing transient servers

- NextJS for building the static results website

If I could build it again I'd consider using something like Azure ML pipelines . See below for an outline of the cloud architecture if you're curious.

Visualization tools

Our models had a lot of stuff that needed to be visualised: inputs, outputs, and calibration targets. Our prior approach was to run a Python script which used matplotlib to dump all the required plots to into a folder. So the development loop to visualise something was:

- Edit the model code, run the model

- Run a Python script on the model outputs

- Open up a folder and look at the plots inside

It's not terrible but there's some friction and toil in there.

Jupyter notebooks were a contender in this space, but I chose to use Streamlit , because many of our plots were routine and standardised. With Streamlit, you can use Python to build web dashboards that generate plots based on a user's input. This was useful for disease modellers to quickly check a bunch of different diagnostic plots when working on the model on their laptop. Given it's all Python (no JavaScript), my colleagues were able to independently add their own plots. This tool went from interesting idea to a key fixture of our workflow over a few months.

A key feature of Streamlit is "hot reloading", which is where the code that generates the dashboard automatically re-runs when you change it. This means you can adjust a plot by editing the Python code, hit "save" and the changes will appear in your web browser. This quick feedback loop sped up plotting tasks considerably.

Aside: This isn't super relevant but while we're here I just want to show off this visualisation I made of an agent based model simulating the spread of a disease through a bunch of households.

Data management

We had quite a variety of data flying around. Demographic inputs like population size, model parameters, calibration targets and the model outputs.

We had a lot of model input parameters stored as YAML files and it was hard to keep them all consistent. We had like, a hundred YAML files when I left. To catch errors early I used Cerberus and later Pydantic to validate parameters as they were loaded from disk. I wrote smoke tests, which were run in CI, to check that none of these files were invalid. I wrote more about this approach here , although now I prefer Pydantic to Cerberus becuase it's a little less verbose.

We had a lot of 3rd party inputs for our modelling such as Google mobility data , UN World Population info, social mixing matrices . Initially this data was kept in source control as a random scattering of undocumented .csv and .xls file. Pre-processing was done manually using some Python scripts. I pushed to get all of the source data properly documented and consolidated into a single folder and tried to encourage a standard framework for pre-processing all of our inputs with a single script. As our input data grew to 100s of megabytes I moved these CSV files to GitHub's Git LFS , since our repo was getting quite hefty and slow to download (>400MB).

In the end hand-rolled a lot of functionality that I probably shouldn't have. If you want to organise and standardise all your input data, I recommend checking out Data Version Control .

Finally I used AWS S3 to store all of the outputs, intermediate values, log files and plots produced by cloud jobs. Each job was stored using a key that included the model name, region name, timestamp and git commit. This was very helpful for debugging and convenient for everybody on the team to access via our results website. The main downside was that I had to occasionally manually prune ~100GB of results from S3 to keep our cloud bills low.

Wrapping Up

Overall I look back on this job fondly. You might have noticed that I've written thousands of words about it. There were some downsides specific to the academic environment. There was an emphasis on producing novel results, especially in the context of COVID in 2020, and as a consequence there were a lot of "one off" tasks and analyses. The codebase was constantly evolving and it felt like I was always trying to catch-up. It was cool working on things that I'd never done before where I didn't know what the solution was. I drew a lot of inspiration from machine learning and data science.

Thanks for reading. If this sounds cool and you think you might like working as a software developer in academia, then go pester some academics.

If you read this and were like "wow! we should get this guy working for us!", I've got good news. I am looking for projects to work on as a freelance web developer. See here for more details.

How to compress images for a webpage

Published: 2021-05-14T12:00:00+10:00

Updated: 2021-05-14T12:00:00+10:00

UTC: 2021-05-14 02:00:00+00:00

URL: https://mattsegal.dev/webpage-image-compressiom.htmlOften when you're creating a website, a client or designer will provide you with large images that are 2-5MB in size and thousands of pixels wide. The large file size of these images will make them slow to load on your webpage, making it seem slow and broken This video …Content Preview

Often when you're creating a website, a client or designer will provide you with large images that are 2-5MB in size and thousands of pixels wide. The large file size of these images will make them slow to load on your webpage, making it seem slow and broken

This video shows you a quick browser-only workflow for cropping, resizing and compressing these images so that they will load more quickly on a webpage. It's not very advanced, but it doesn't need to be. Here I convert images from ~2MB to ~100kB, which is a ~20x reduction in file size.

How to setup Django with React

Published: 2020-10-24T12:00:00+11:00

Updated: 2020-10-24T12:00:00+11:00

UTC: 2020-10-24 01:00:00+00:00

URL: https://mattsegal.dev/django-react.htmlIt's not too hard to get started with either Django or React. Both have great documentation and there are lots of tutorials online. The tricky part is getting them to work together. Many people start with a Django project and then decide that they want to "add React" to it …Content Preview

It's not too hard to get started with either Django or React. Both have great documentation and there are lots of tutorials online. The tricky part is getting them to work together. Many people start with a Django project and then decide that they want to "add React" to it. How do you do that though? Popular React scaffolding tools like Create React App don't offer you a clear way to integrate with Django, leaving you to figure it out yourself. Even worse, there isn't just one way to set up a Django/React project. There are dozens of possible methods , each with different pros and cons. Every time I create a new project using these tools I find the options overwhelming.

I think that most people should start with a setup that is as close to vanilla Django as possible: you take your existing Django app and sprinkle a little React on it to make the frontend more dynamic and interactive. For most cases, creating a completely seperate "single page app" frontend creates a lot of complexity and challenges without providing very much extra value for you or your users.

In this series of posts I will present an opinionated guide on how to setup and deploy a Django/React webapp. The focus will be on keeping things simple, incremental and understanding each step. I want you to be in a position to debug any problems yourself. At the end of each post, you should have a working project that you can use.

I'm going to assume that you know:

- the basics of web development (HTML, CSS, JavaScript)

- the basics of Django (views, templates, static files)

- the basics of React (components, props, rendering)

I'm not going to assume that you know anything about Webpack, Babel, or any other JavaScript toolchain insanity.

Example project

The example code for this guide is hosted on this GitHub repo . The code for each section is available as a Git branch:

Before you start the rest of the guide, I recommend setting up the example project by cloning the repo and following the instructions in the README :

git clone https://github.com/MattSegal/django-react-guide.gitDjango and static files

Before we dig into React, Babel and Webpack, I want to make sure that we have a common understanding around how static files work in Django:

The approach of this guide will be to re-use a lot of this existing setup. We will create an additional that system inserts our React app's JavaScript into a Django static files folder.

Why can't we just write React in a single static file?

Why do we need to add a new system? Django is pretty complicated already. Can't we just write our React app in a single JavaScript file like you usually do when writing JavaScript for webpages? The answer is yes, you totally can! You can write a complete React app in a single HTML file:

<html> <body> <!-- React mount point --> <div id="app"></div> <!-- Download React library scripts --> <script crossorigin src="https://unpkg.com/react@16/umd/react.development.js"></script> <script crossorigin src="https://unpkg.com/react-dom@16/umd/react-dom.development.js"></script> <script> // Define the React app const App = () => { const [count, setCount] = React.useState(0) const onClick = () => setCount(c => c + 1) return React.createElement('div', null, React.createElement('h1', null, 'The count is ' + count), React.createElement('button', { onClick: onClick }, 'Count'), ) } // Mount the app to the mount point. const root = document.getElementById('app') ReactDOM.render(React.createElement(App, null, null), root) </script> </body> </html>Why don't we just do this? There are a few issues with this approach of writing React apps:

- We can't use JSX syntax in our JavaScript

- It's harder to break our JavaScript code up into modules

- It's harder to install/use external libraries

Webpack

The example code for this section starts here and ends here .

We need a tool that helps us use JSX, and it would be nice to also have a "module bundling system" which lets us install 3rd party libraries and split our JavaScript code up into lots of little files. For this purpose, we're going to use Webpack . Webpack is going to take our code, plus any 3rd party libraries that we want to install and combine them into a single JS file.

In this step we will just to create a minimal working Webpack setup. We're not goint try to use React yet. By the end of this section, we won't have added any new JavaScript features, but Webpack will be working.

To use Webpack you need to first install NodeJS so that you can run JavaScript outside of your web browser. You need to be able to run

nodeandnpm(the Node Package Manager) before you can continue.First, go into the example project and create a new folder called

frontend. We'll start by just copying over the existing JavaScript that is used by the Django app in main.js . We're going to copy this into a "source code" folder atfrontend/src/index.js.// frontend/src/index.js const btn = document.getElementById('click') btn.addEventListener('click', () => alert('You clicked the button!'))Inside of the

frontendfolder, install Webpack usingnpmas follows:npm init --yes npm install webpack webpack-cliNow is a good time to update your

.gitignorefile to excludenode_modules. Next, we need to add a file that tells Webpack what to do, which is calledwebpack.config.js// frontend/webpack.config.js const path = require('path') const webpack = require('webpack') module.exports = { // Where Webpack looks to load your JavaScript entry: { main: path.resolve(__dirname, 'src/index.js'), }, mode: 'development', // Where Webpack spits out the results (the myapp static folder) output: { path: path.resolve(__dirname, '../backend/myapp/static/myapp/'), filename: '[name].js', }, plugins: [ // Don't output new files if there is an error new webpack.NoEmitOnErrorsPlugin(), ], // Where find modules that can be imported (eg. React) resolve: { extensions: ['*', '.js', '.jsx'], modules: [ path.resolve(__dirname, 'src'), path.resolve(__dirname, 'node_modules'), ], }, }Finally let's make it easy to run Webpack by including an entry in the "scripts" section of our

package.jsonfile:// frontend/package.json { // ... "scripts": { "dev": "webpack --watch --config webpack.config.js" }, // ... }The

--watchflag is particularly useful: it makes Webpack re-run automatically on file change. Now we can run Webpack usingnpm:npm run devYou will now see that the contents of your

main.jsfile has been replaced with a crazy lookingevalstatement. If you check your Django app athttp://localhost:8000you'll see that the JavaScript on the page still works, but it's now using the Webpack build output athttp://localhost:8000/static/myapp/main.js// backend/myapp/static/myapp/main.js eval("const btn = document.getElementById('click')\nbtn.addEventListener('click', () => alert('You clicked the button!'))\n\n\n//# sourceURL=webpack://frontend/./src/index.js?");This file is the Webpack build output. Webpack has taken our source file (

index.js) and transformed it into an output file (main.js):

So now we have Webpack working. It's not doing anything particularly useful or interesting yet, but all the plumbing has been set up.

Source code vs. build outputs

It's a common newbie mistake to add Webpack build outputs like

main.jsto source control. It's a mistake because source control is for "source code", not "build artifacts". A build artifact is a file created by a build or compliation process. The reason you don't add build artifacts is because they're redundant: they are fully defined by the source code, so adding them just bloats the repo without adding any extra information. Even worse, having a mismatch between source code and build artifacts can create nasty errors that are hard to find. Some examples of build artifacts:

- Python bytecode (.pyc) file,s which are built from .py files by the Python interpeter

- .NET bytecode (.dll) files, built from compiling C# code

- Executable (.exe) files, build from compiling C code

None of these things should go in source control unless there's a special reason to keep them. In general they should be kept out of Git using the

.gitignorefile.My approach for this project is to create a special Webpack-only folder in Django's static file called "build", which is ignored by Git. To achieve this, you need to update your

webpack.config.jsfile:// frontend/webpack.config.js // ... module.exports = { // ... output: { path: path.resolve(__dirname, '../backend/myapp/static/myapp/build/'), filename: '[name].js', }, // ... }You will need to restart Webpack for these changes to take effect. Then you can add

build/to your.gitignorefile. Finally, you will need to update the static file link in your Django template:<!-- backend/myapp/templates/myapp/index.html --> <script src="{% static 'myapp/build/main.js' %}"></script>Adding React

The example code for this section starts here and ends here .

Now that Webpack is working, we can add React. Let's start by installing React in our

frontendfolder:npm install react react-domNow we can use React in our JavaScript source code. Let's re-use the small counter app I created earlier:

// frontend/src/index.js import React from 'react' import ReactDOM from 'react-dom' // Define the React app const App = () => { const [count, setCount] = React.useState(0) const onClick = () => setCount(c => c + 1) return React.createElement('div', null, React.createElement('h1', null, 'The count is ' + count), React.createElement('button', { onClick: onClick }, 'Count'), ) } // Mount the app to the mount point. const root = document.getElementById('app') ReactDOM.render(React.createElement(App, null, null), root)Now if you go to

http://localhost:8000/you should see a simple counter. If you inspect the contents ofmain.jsathttp://localhost:8000/static/myapp/build/main.js, you'll see that there is a lot more stuff included in the file. This is because Webpack has bundled up our code plus the development versions of React and ReactDOM into a single file:

Adding Babel

Next we need at tool that lets us write JSX. We want to be able to write our React components like this:

const App = () => { const [count, setCount] = React.useState(0) const onClick = () => setCount(c => c + 1) return ( <div> <h1>The count is {count}</h1> <button onClick={onClick}>Count</button> </div> ) }and then some magic tool transforms it into regular JavaScript, like this:

const App = () => { const [count, setCount] = React.useState(0) const onClick = () => setCount(c => c + 1) return React.createElement('div', null, React.createElement('h1', null, 'The count is ' + count), React.createElement('button', { onClick: onClick }, 'Count'), ) }That magic tool is Babel , a JavaScript compiler that can transform JSX into standard JavaScript. Babel can use plugins , which apply custom transforms to your source code. It also offers presets , which are groups of plugins that work well together to achieve a goal.

Now we're going to install a whole bunch of Babel stuff with

npm:npm install --save-dev babel-loader @babel/core @babel/preset-reactWhat the hell is all of this? Let me break it down for you:

- @babel/core : The main Babel compiler library

- @babel/preset-react : A collection of React plugins: tranforms JSX to regular JavaScript

- babel-loader : Allows Webpack to use Babel

These are not the only Babel plugins that I like to use, but I didn't want to add too many new things at once. In addition to installing the plugins/presets, we need to tell Babel to use them, which we do with a config file called

.babelrc.// frontend/.babelrc { "presets": ["@babel/preset-react"] }Next, we need to tell Webpack to use our new Babel compiler for all our JavaScript files:

// frontend/webpack.config.js // ... module.exports = { // ... // Add a rule so Webpack reads JS with Babel module: { rules: [ { test: /\.js$/, exclude: /node_modules/, use: ['babel-loader'], }, ]}, // ...Essentially, this config change tells Webpack: "for any file ending with

.js, usebabel-loaderon that file, expect for anything innode_modules". Finally, we can now use JSX in our React app:// frontend/src/index.js import React from 'react' import ReactDOM from 'react-dom' // Define the React app const App = () => { const [count, setCount] = React.useState(0) const onClick = () => setCount(c => c + 1) return ( <div> <h1>The count is {count}</h1> <button onClick={onClick}>Count</button> </div> ) } // Mount the app to the mount point. const root = document.getElementById('app') ReactDOM.render(<App />, root)You will need to restart Webpack for the config changes to be loaded. After that, you should be able to visit

http://localhost:8000/and view your counter app, now working with JSX.Deployment

I won't cover deployment in detail in this post, because it's long enough already, but in short, you can now deploy your Django/React app as follows:

- Install JavaScript dependencies with

npm- Run Webpack to create build artifacts in your Django static files

- Deploy Django how you normally would

There a few things that it would be good to change before deploying, like not using "development" mode in Webpack, but this workflow should get you started for now. If you have never deployed a Django app before, I've written an introductory guide on that as well, which uses the same incremental, explanation-heavy style as this guide.

Next steps

There is a lot of stuff I didn't cover in this guide, which I'd like to write about in the future. Here are some things that I didn't cover, which are important or useful when building a React/Django app:

- Hot reloading

- Deployment

- Passing requests/data between Django and React

- Modular CSS / SCSS / styled components

- Routing and code-splitting

- Authentication

How to highlight unused Python variables in VS Code

Published: 2020-10-09T12:00:00+11:00

Updated: 2020-10-09T12:00:00+11:00

UTC: 2020-10-09 01:00:00+00:00

URL: https://mattsegal.dev/pylance-vscode.htmlI make a lot of stupid mistakes when I'm working on Python code. I tend to: make typos in variable names accidently delete a variable that's used somewhere else leave unused variables lying around when they should be deleted It's easy to accidentally create code like in the image below …Content Preview

I make a lot of stupid mistakes when I'm working on Python code. I tend to:

- make typos in variable names

- accidently delete a variable that's used somewhere else

- leave unused variables lying around when they should be deleted

It's easy to accidentally create code like in the image below, where you have unused variables (

y,z,q) and references to variables that aren't defined yet (z).

You'll catch these issues when you eventually try to run this function, but it's best to be able to spot them instantly. I want my editor to show me something that looks like this:

Here you can see that the vars

y,zandqare greyed out, to show that they're not used. The undefined reference tozis highlighted with a yellow squiggle. This kind of instant visual feedback means you can write better code, faster and with less mental overhead.Having your editor highlight unused variables can also help you remove clutter. For example, it's common to have old imports that aren't used anymore, like

copyandrequestsin this script:

It's often hard to see what imports are being used just by looking, which is why it's nice to have your editor tell you:

You'll also note that there is an error in my import statement.

import copy from copyisn't valid Python. This was an unintentional mistake in my example code that VS Code caught for me.Setting this up with VS Code

You can get these variable highlights in VS Code very easily by installing PyLance , and alternative "language server" for VS Code. A language server is a tool, which runs alongside the editor, that does static analysis of your code.

To get this language server, go into your extensions tab in VS Code, search for "pylance", install it, and then you'll see this popup:

Click "Yes, and reload".

Alternatives

PyCharm does this kind of static analysis out of the box. I don't like PyCharm quite so much as VS Code, but it's a decent editor and many people swear by it. You can also get this feature by enabling a Python linter in VS Code like flake8, pylint or autopep8. I don't like twiddling with linters, but again other people enjoy using them.

Next steps

If you're looking for more Python productivity helpers, then check out my blog post on the Black auto-formatter.

A Django project blueprint to help you learn by doing

Published: 2020-10-03T12:00:00+10:00

Updated: 2020-10-03T12:00:00+10:00

UTC: 2020-10-03 02:00:00+00:00

URL: https://mattsegal.dev/django-survey-project.htmlThere's an awkward point when you're learning Django where you've done the official tutorial and maybe built a simple project, like a to-do list, and now you want to try something a little more advanced. People say that you should "learn by building things", which is good advice, but it …Content Preview

There's an awkward point when you're learning Django where you've done the official tutorial and maybe built a simple project, like a to-do list, and now you want to try something a little more advanced. People say that you should "learn by building things", which is good advice, but it leaves you unsure about what to actually build .

In this post I'll share two things:

- a description of a Django project for beginners, which you can build; and

- a short guide on how to design a new website from scratch

I won't introduce many new tools or technical concepts beyond what is already in the Django tutorial. The project can be built using just the basic Django features. There is no need to use REST Framework, JavaScript, React, Webpack, Babel, JSON or AJAX to get this done. Only Django, HTML and CSS are required.

Even though this project only uses simple tools, I think building it is worthwhile for a beginner, since it will introduce you to many of the common themes of backend web development.

Project overview

In this project, you will build a Django app that runs a survey website. On this site, users can create surveys and send them out to other people to get answers. A user can sign up, create a survey and add multi-choice questions to it. They can then send a survey link to other people, who will answer all the questions. The user who created the survey can see how many people answered, and what percentage of people chose each multi-choice option.

That's the whole app. I have created a reference implementation on my GitHub which you can look at if you get stuck when building it yourself.

The project description sounds simple, doesn't it? I thought this would take me 8 hours to design and build, but I spent 20 hours at the keyboard to get it done. Software projects are hard to estimate before they are built, since they have a surprising amount of detail that you don't think about beforehand.

Designing the app

So now you know what you're building, but you're not ready to write any code yet. We need to create a design first. As the saying goes: weeks of coding can save hours of planning .

This design will have three parts:

- User journeys : where you decide who is using your app and how they will use it

- Data models : where you decide how you will structure the database

- Webpage wireframes : where you decide what your user interface (UI) will look like

User journey

The most important thing to do when building a website is to consider the users and their goals. In this case, I think there are two sets of users:

- Survey takers : people who want to answer a survey's questions

- Survey creators : people who want to create a survey, send it out and view the answers

To better understand who your users are and what they want, you should construct a user journey for each of them: a high-level description of the steps that they will need to take to get what they want. This is easily represented as a diagram, created with a free wireframing tool like Exalidraw or Wireflow .

Let's start with the person who is answering the survey, the "survey taker", who has a simple user journey:

Next, let's look at the person who created the survey, the "survey creator":

Creating these diagrams will force you to think about what you will need to build and why. For example, a survey creator will probably need a user account and the ability to "log in", since they will want private access to their surveys. Lots of thoughts about how to build your app will cross your mind when you are mapping these user journeys.

Data models

Once you know what your users want to do, you should focus on what data you will need to describe all of the things in your app. So far we have vague ideas of "surveys", "questions", "answers" and "results", but we need a more specific description of these things so that we can write our Model classes in Django.

To better understand your data, I recommend that you create a simple diagram that displays your models and how they relate to each other. Each connection between a model is some kind of foreign key relation. Something like this:

I explain how I came up with this particular data model in this appendix page .

You don't need to get too formal or technical with these diagrams. They're just a starting point, not a perfect, final description of how your app will work. Also, the data model which I made isn't the only possible one for this app. Feel free to make your own and do it differently.

Webpage wireframes

Now we have an idea of how our users will interact with the app and we know how we will structure our data. Next, we design our user interfaces. I suggest you create a rough wireframe that describes the user interface for each webpage. Creating wireframes for webpages is a good idea for two reasons:

- Wireframing allows you to quickly explore different page designs and it forces you to think about how your app needs to work

- It's much easier to write HTML and CSS for pages where you already have a simple design to work from

You can use a free wireframing tool like Exalidraw or Wireflow for these diagrams. Keep in mind that this project doesn't use JavaScript, so you can't get too fancy with custom interactions. You will need to use HTML forms to POST data to the backend.

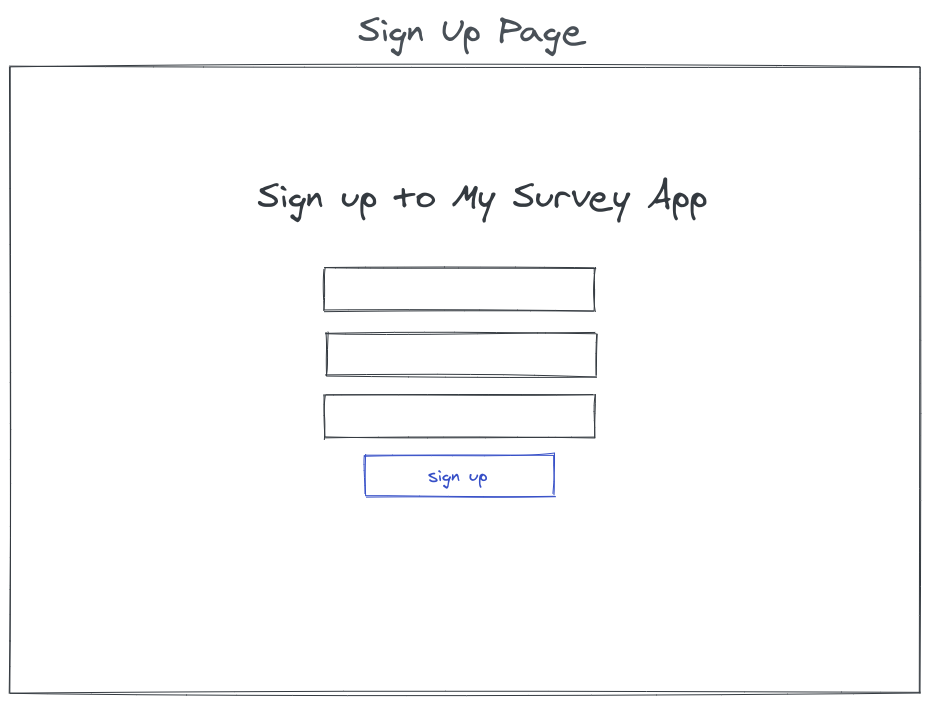

You can create your own wireframes or you can use the ones that I've already created, which are all listed in this appendix page with some additional notes for each page:

- Starting the survey

- Answering the survey

- Survey submitted

- Landing page

- Signing up

- Logging in

- Survey list

- Create a survey

- Edit a survey

- Add questions to a survey

- Add options to a survey question

- Survey details

General advice

Now with some user journeys, a data model and a set of wireframes, you should be ready to start building your Django app. This project blueprint will help you get started, but there is still a lot of work for you to do if you want to build this app. You still need to:

- decide on a URL schema

- create models to represent the data

- create forms to validate the user-submitted data

- write HTML templates to build each page

- add views to bind everything together

There's about 12 views, 12 templates, 5 forms and 5 models to write. Given all this work, it's really important that you focus and keep the scope of this project narrow. Keep everything simple . Don't use any JavaScript and write as little CSS as possible. Use a CSS framework like Boostrap or Semantic UI if you want it to look nice. Get something simple working first , and then you can make it fancy later. If you don't focus, you could spend weeks or months on this project before it's done.

As a specific example, consider the user authentication feature. In this app, your users can log in or sign up. To really make the auth system "complete", you could also add a log out button, a password reset page, and an email validation feature. I think you should skip these features for now though, and get the core functionality working first.

Software projects are never finished, and you can improve this app again and again even after you are "done". Don't try to make it perfect, just finish it.

Next steps

I hope you find this blueprint project and design guide helpful. If you actually end up building this, send me an email! I'd love to see it. If you like this post and you want to read some more stuff I've written about Django, check out:

- A beginner's guide to Django deployment

- How to read the Django documentation

- How to make your Django project easy to move and share

- How to polish your GitHub projects when you're looking for a job

- Tips for debugging with Django

You can also subscribe to my mailing list below for emails when I post new articles.

Django project blueprint: data model

Published: 2020-10-03T12:00:00+10:00

Updated: 2020-10-03T12:00:00+10:00

UTC: 2020-10-03 02:00:00+00:00

URL: https://mattsegal.dev/django-survey-project-data-model.htmlThis post is an appendix to my post on designing a Django project. In this page I explain why I chose to use this data model: I created this data model by looking at the user journeys and thinking about what data I would need to make them work. Here's …Content Preview

This post is an appendix to my post on designing a Django project . In this page I explain why I chose to use this data model:

I created this data model by looking at the user journeys and thinking about what data I would need to make them work. Here's the thought process I used. First I thought about the data that I need to define everything about a "survey" in the app. I decided that I would need:

- a Survey model to represent each survey; and then

- a link between each Survey and a User , since we need to restrict survey access to only the user who owns it

- a Question model for each question on the survey. Each survey needs to have one or more questions, so we can't hardcode questions as fields on the Survey model, so we must create a new Question model which knows which survey owns it

- each Question has one re more multi-choice answer options, so we must create an Option model

Next, I thought about how we would record a survey taker answering the questions. We would need:

- a Submission model to represent each survey taker's submission

- a link between Submission and Survey , so each submission can know which survey it belongs to

- the Answers to each question, where the answer is for a particular Option

Django project blueprint: wireframes

Published: 2020-10-03T12:00:00+10:00

Updated: 2020-10-03T12:00:00+10:00

UTC: 2020-10-03 02:00:00+00:00

URL: https://mattsegal.dev/django-survey-project-wireframes.htmlThis post is an appendix to my post on designing a Django project. This page shows all the wireframes for the app, with some additional notes for each page. Page designs for the user who answers the survey This section covers the pages required for the "survey taker" user journey …Content Preview

This post is an appendix to my post on designing a Django project . This page shows all the wireframes for the app, with some additional notes for each page.

Page designs for the user who answers the survey

This section covers the pages required for the "survey taker" user journey:

Taken literally, this journey suggests that we should build ~3 pages.

Starting the survey